Europe’s last-mile parcel delivery system is approaching a structural breaking point. Rapid growth in e-commerce, driven by platforms such as Amazon, Temu, and Shein, combined with the expansion of recommerce via players like Vinted and eBay, and return-intensive fashion flows from Zalando, H&M, and ZARA, is overwhelming traditional door-to-door delivery and parcel shop models. As volumes rise, delivery networks are hitting capacity constraints, and costs and labor are increasing. Out-of-home (OOH) delivery, particularly parcel lockers, is emerging not as a convenience, but as essential infrastructure for the future of European logistics. Kearney presents a market overview.

Locker delivery improves productivity, reduces delivery costs, and increases predictability in the last mile. Evidence from early-adopter markets shows that once locker density and service reliability reach a critical threshold, consumer uptake accelerates rapidly. Surveys indicate that consumers already prefer lockers as a shared pickup option when available nearby. The main barrier is not demand, but insufficient network density.

Despite this clear potential, Europe’s locker expansion is being slowed primarily by regulatory and permitting constraints. Municipal approval processes vary widely between cities and even districts, with different rules on design, siting, fees, and timelines. These procedures are often opaque and slow, particularly in high-impact locations such as public spaces and mobility hubs. As a result, locker networks struggle to reach the scale needed for system-wide impact, even where parcel volumes and consumer interest are high.

Parcel shops remain the dominant OOH channel today, but their scalability is limited. Many shops withdraw from parcel services each year due to staffing pressure, space constraints, and operational disruption. Limited opening hours reduce convenience, especially during peak periods such as lunch breaks and weekends, while queues and curbside congestion undermine service quality. As parcel volumes continue to grow, shops alone cannot absorb future demand. Automated, always-on alternatives are required, according to Kearney.

Parcel lockers offer distinct advantages. They operate 24/7, require minimal staffing, and can be deployed in a wide range of locations. Lockers enable higher “drop factors”—more parcels delivered per stop—allowing carriers to redesign routes, reduce variability, and lower costs. They are especially valuable for recommerce flows, where lockers already account for 30–60 percent of first-mile deliveries in more mature markets.

Two locker models dominate: closed networks operated by single carriers, and open networks shared by multiple operators. Closed networks demand high investment and delivery density, favoring large incumbents. Open networks lower entry barriers, pool volumes and make better use of scarce prime locations. Although carriers are sometimes reluctant to share infrastructure, open access often delivers superior economics and faster network growth.

Financially, locker deployment is becoming increasingly attractive. Payback periods have fallen from around three years to roughly two years, driven by higher utilization and new revenue models. Retailers such as IKEA use lockers for click-and-collect to manage peak demand and reduce in-store congestion, while platforms like Vinted incentivize locker use with lower prices. Crucially, lockers are not just an urban solution: in suburban, rural and low-density areas, long driving distances and failed deliveries make lockers at supermarkets, petrol stations and public transport hubs particularly valuable. In such contexts, targeted public co-funding can accelerate coverage and prevent inefficient delivery patterns from becoming entrenched.

The contrast across Europe is stark. Poland and the Czech Republic demonstrate what dense, mature locker networks can achieve. Meanwhile, high-volume markets such as Germany, the UK, the Netherlands, and Austria show large “white spaces” where parcel demand is high but locker density remains low. Germany illustrates both the opportunity and the challenge. With more than three billion B2C parcels annually, locker penetration remains modest. Major players include DHL, which operates a largely closed network and plans price incentives for locker delivery from 2026; Amazon, which may expand or partner to meet growing OOH demand; and carriers such as Hermes, GLS, and DPD, which increasingly rely on shared networks to improve profitability.

Analysis of Germany suggests that commercial locker locations are nearing saturation, while residential and public spaces remain vastly underdeveloped, primarily due to regulatory complexity. Inconsistent permitting, unclear responsibilities, and legacy rules on public space are now the main bottlenecks to scaling.

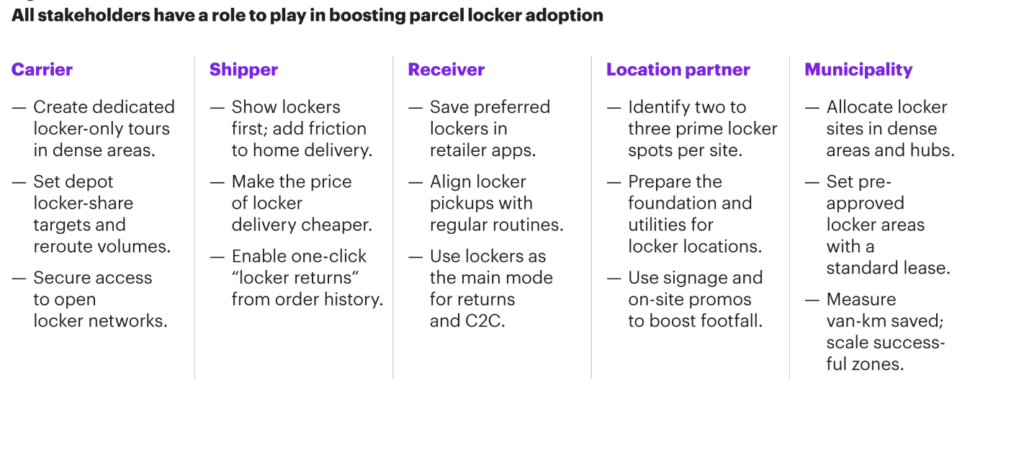

According to Kearney, Europe’s locker potential is constrained not by technology or consumer acceptance, but by governance. Unlocking growth requires standardized permits, transparent rules, and coordinated action between cities, states, carriers, and property owners. Markets that move decisively will gain more efficient logistics, lower costs, cleaner air, and quieter streets. Those who hesitate risk locking themselves into increasingly fragile and expensive last-mile systems.

Unfortunately, Kearney completely ignores the mobility impact of people picking up parcels by car and the impact on local retail… Placing lockers in public spaces is not necessarily disadvantageous, and a shared vision between municipalities and parcel deliverers is needed. Behavioral change is essential to ensure the success of any new system. And… the most crucial question: why would a municipality support online shopping instead of supporting local stores?

Source: Kearney

Also read: What role can municipalities play in implementing parcel lockers?