Online shopping at large retailers in the United States is 17% more carbon-efficient than visiting traditional stores, according to Generation Investments Management. Their study finds that the integration of efficient logistics and warehousing gives e-commerce the advantage.

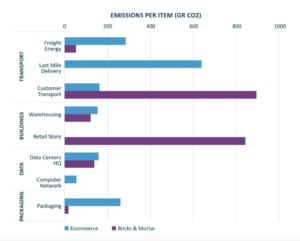

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for e-commerce are 17% lower than bricks and mortar retail in a base case scenario. This is according to a new modeling tool developed for Generation Investment Management LLP by leading experts in the field. Grounded in detailed assumptions about energy consumption and GHG emissions in the supply chain, the tool compares the footprint of an item sold by traditional retailers with one delivered via e-commerce.

Brick-and-mortar stores

E-commerce comes out around 140 gram CO2/unit above bricks and mortar for transport overall. Instead, the key differentiating factor is the higher energy demand at bricks and mortar stores (for lighting, heating, and cooling). E-commerce uses more energy than bricks and mortar for warehousing, but only by a relatively small amount. This leaves e-commerce with an 800 gram CO2 lower emissions footprint from buildings overall. This more than outweighs the higher emissions for e-commerce in transport, data use, and packaging. Importantly, it is not so much these individual steps in the logistics chain, but rather the overall system efficiency that matters.

Scale and time

It’s important to realize that the research focused on the largest-scale retail players. The assumptions are based on estimates of real-world performance for major traditional retailers (such as Target and Walmart) as well as large e-commerce companies (which, given its prominence, are particularly based on Amazon). In the model, e-commerce achieves this advantage through the efficiencies achieved at a global scale. In fact, when they model a smaller scale e-commerce company, it comes out slightly more emissions-intensive than their base case for bricks and mortar, in large part due to less efficient last-mile delivery.

Another key issue is timing. Rapid deliveries tend to increase energy use per item. To get to the consumer at short notice, some products may need to be transported by air. And, at the other end of the chain, last-mile delivery vehicles can be driving around half-empty. On the other hand, companies with global logistics operations are building local fulfillment centers where goods await future orders. The flexibility in their distribution systems can – at least in theory – achieve next-day deliveries without the need for air freight and with energy-efficient last-mile delivery.

Consumer behavior

The model suggests that shopping online is typically more GHG-efficient than shopping at brick-and-mortar stores. But there are all sorts of contextual factors that determine the footprint of a single ‘shopping instance’. The researchers believe many of these factors represent opportunities to cut emissions through changes in consumer behavior.

Basket size (how many items you buy in a single visit to a physical or online store) has a big effect. In their base case the physical retail basket contains 2.5 items and online has 1.2 items. If you increase the physical basket size to five items, a tipping point occurs – bricks and mortar becomes less ‘emissions intensive’ than online delivery. That’s because the per-item emissions from customer travel are spread across multiple items.

The distance traveled by bricks and mortar shoppers also matters. Drive a few kilometers to a local store and you are certainly not helping your retail GHG footprint. On the flip side, if you take public transport or walk to the local shops, the footprint is probably lower than if you bought those items online. Unfortunately, this is relatively uncommon in the US. Of course, you can also visit more than one shop in a single trip. This issue of ‘trip chaining’ is quite tricky to capture. Recent surveys conducted by UC Davis indicate that chaining cuts the typical ‘distance traveled’ per unit purchase by two-thirds. This is reflected in our base case.

The rate of returns from online shopping has an effect in the model, but it’s not as much as you might think. The researchers assume a 20% return rate for e-commerce in the base case. Although there is some additional energy spent on ‘reverse logistics’ (collecting items from the customer), it’s not a dead loss – many of those items go back to the warehouse or store ready to be re-sold. This could quickly become a bigger problem for the GHG footprint if logistics need to be expanded or if many items are destroyed.

To recap, you – as a consumer – have meaningful opportunities to minimize your GHG footprint by being patient with delivery, avoiding multiple shopping trips to bricks and mortar stores, and returning items only where necessary. At the same time, retailers can do more to make these choices attractive – for instance, via price signals and delivery times.

Conclusions

Online shopping has a lower carbon footprint today. But as the researchers have seen, there are a lot of elements to this story. First, they want to see concrete steps taken by companies to ensure a rapid transition to net-zero emissions. Switching to electric vehicles for last-mile delivery should be a priority for e-commerce companies, along with powering data centers with renewable energy and cutting out single-use packaging. Second, the final frontier for all retailers is enabling sustainable consumption patterns. Given their capabilities in technology and data, e-commerce companies are only scratching the surface of what could be done with better environmental accounting. Third, they suggest enhanced disclosure of GHG data in the supply chain. E-commerce companies are especially well placed to unlock accurate accounting of environmental impact, given their innovative capacity in data and technology.

In the meantime, customers can make a meaningful difference today through their purchasing behavior. It’s best to avoid long drives to buy one or two items from a bricks-and-mortar store. When shopping online, it’s about avoiding urgent shipments and excessive returns. Perhaps most of all, it’s about what consumers choose to buy.

Source: Generation Investments Management.