More European cities see construction logistics as part of urban freight policies, but also a lot of European cities do not have any initiatives yet. However, the awareness to deal with urban construction logistics is growing. These are the conclusions of the latest SUCCESS-report on the experience and maturity of 12 European cities in construction logistics.

Experience and maturity

During workshops, an analysis of the state of the art was carried out in terms of problems and opportunities in transport optimisation in the construction sector. Twelve European cities like Rome, London, Antwerps, Graz and Brussels were introduced to the project’s roadmap and best practices and, after a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) analysis of their local contexts, cities’ representatives were involved in a joint problem solving exercise for the evaluation of specific measures and best practices (in terms of impact and applicability) to improve construction logistics in their jurisdictions.

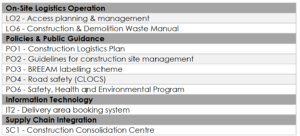

The 12 cities presented different levels of experience and maturity in construction logistics and using best practices (see table below). The researchers found that the involved northern EU cities have more experience both in terms of construction logistics practices which are in place, and in terms of inclusion of construction logistics in mobility planning.

Construction consolidation centres

With specific reference to Construction Consolidation Centres (CCC), the practice raised significant interest among the stakeholders. Cities indicated that their role in CCCs should mainly be that of fostering CCCs use by:

- Procuring public works, as leverage to foster sustainable practices in the construction sector, in terms of requirements for contractors and bidding creria;

- Planning areas for CCCs, as a medium and long-term perspective securing logistics areas;

- Developing rules and standards which can create a market for CCCs, similarly to the cases of Urban Consolidation Centres for other supply chains (e.g. retail, food).

This indicates how Cities do not think that they should fund CCCs; one reason is the lack of public funding, but our understanding is that Cities consider CCCs as a business activity which are in private companies’ domain. Moreover, in case authorities would operate CCCs, this may bring market distortion issues.

The stakeholders identified three key factors concerning the implementation of CCCs:

Market

CCC’s financial sustainability is a core issue. The dimension of the construction sites served by the CCC will drive the expected CCC’s transport demand. Participants noted how a permanent CCC business may rely on a variable demand compared to other types of consolidation platforms. Moreover, the presence of major construction sites will ease CCC sustainability, by ensuring demand for its services and the possibility to develop economies of scale and related business sustainability. In this sense the dimension of the construction sector in a city and the presence of specific big construction projects are facilitating factors.

Location

Further than an issue of driving time – distance (and related transport costs) from CCCs to construction sites, an important element contributing to the CCC’s financial sustainability is the value of the land where it will be located. In particular, if the CCC area is the city centre and if this is sold at market prices for commercial activities (which are higher than those for areas normally dedicated to logistics activities), this may make the CCC initiative not profitable. In this sense, as reported above, authorities may act to secure acceptable land prices (for example with financial support for their acquisition) or to make land available to CCC initiatives.

Supply chain

Introducing CCCs brings change in construction companies’ supply chains (construction companies, suppliers and transportation companies). Currently, according to the ETP participating construction companies, there are not sufficient evidences to assess if CCCs are viable and profitable. Moreover, CCCs’ introduction may impact not only logistics operations, but also buying processes and related contracts. In particular, CCCs impact on contracts with logistics providers and with other suppliers, moving CCC’s costs within the supply chain and requiring contractual changes.

Public private partnership

Public authorities can act in three ways: adopting regulations which foster sustainable construction logistics solutions, guiding businesses in adopting sustainable construction logistics solutions and being active in logistics operations. Past urban consolidation centres (UCC) experience shows how the private sector should be in charge of their financial sustainability. Nevertheless, the public sector maintains a role in starting up construction logistics improvements and eventually CCCs.

The role and involvement level of municipalities in construction logistics issues highly depend on whether the work is from a city public tender or from a private actor. Public procurement is an important leverage for the public sector to foster sustainable practices in the construction sector, in terms of requirements for contractors and bidding criteria.

Credibility fosters compliance and business engagement. A highly credible public sector is a facilitating factor to engage businesses in new initiatives. Also, credibility of public actors comes with skills in construction and construction logistics.

Future perspectives

The SUCCESS workshops showed that despite construction logistics being a niche topic, many EU cities are engaging or have interest in facing the challenges related to transport impacts of the construction sector. Currently the involved cities’ perspective to construction logistics is more targeted to traffic management, rather than to supply chain management. This is in line with local authorities’ statutory competences.

Nevertheless, the workshops showed promising developments both in terms of specific construction logistics practices in the involved cities and in terms of inclusion of the construction logistics topic within their mobility and logistics planning tools.

Your can download the full report here.